The Union Label—From Tiger to Tabby

By Frank Glassner | 2025-09-01

Prologue – The Roar That Once Was

Happy Labor Day Sports Fans!

Yes, the symbolic end of summer, when the grills cool, the flip-flops retire, and everyone pretends they’re excited to go “back to work” and “back to school.” (Translation: digging out last year’s lunchbox, hoping it doesn’t still contain an uneaten PB&J fossil.) I trust you all had your share of beaches, barbecues, ball games, or at least one blissful afternoon where you weren’t forced to answer emails while pretending to admire fireworks. So, here’s to you: the survivors of summer, now marching back into offices, classrooms, and the strange purgatory of Zoom calls.

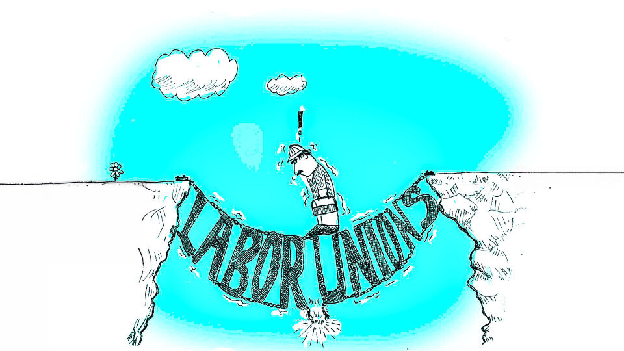

And what better day than Labor Day—the holiday born of labor unions themselves—to talk about unions? Or rather, to perform the post-mortem. Once upon a time, they were roaring tigers: fierce, fanged, fire-breathing beasts that built the American middle class. Today? More like the neighborhood stray tabby—skittish, meowing, clawless, and occasionally biting its own tail.

It wasn’t always so. At the dawn of the 20th century, unions weren’t punchlines; they were lifelines. Samuel Gompers, cigar smoke curling around his head, demanded “more” not just in wages but in dignity. Eugene V. Debs, the socialist locomotive of the Pullman strike, thundered about justice for the working man. Mother Jones—yes, that Mother Jones, “the most dangerous woman in America”—rallied miners and children against conditions so brutal they make Amazon warehouses look like summer camps. Cesar Chavez fasted in fields, Walter Reuther led auto workers to glory, and George Meany puffed cigars in Washington as if he were the government. For better or worse, unions were the soundtrack to America’s industrial adolescence: defiant, gritty, unapologetic.

The romance was real. Breadlines turned into breadwinners. Twelve-hour shifts turned into forty-hour weeks. Kids traded coal mines for classrooms. For a moment—just a glittering, golden postwar moment—it seemed like solidarity was not just a slogan but a working formula for American prosperity.

But as with all human institutions, the script flipped. What began as a noble cause ossified into bureaucracy, corruption, and entitlement. Unions discovered the joys of being gatekeepers, of flexing not for fairness but for power. The mob moved in—literally, in the case of Jimmy Hoffa, who still hasn’t been located despite more digging than an archaeological site at Pompeii. Contracts became anchors. Strikes became kamikaze missions. And companies, tired of being held hostage, learned a new trick: pack up the toys and move the factory to Mexico, China, or anywhere the word “collective bargaining” didn’t translate.

So here we are, on this Labor Day, staring at the corpse of a once-mighty juggernaut. Sam Gompers is spinning, Debs is howling, Chavez is fasting in the afterlife, Reuther is drafting a grievance, and Hoffa—wherever he is—probably wishes someone would at least let him vote on the next contract.

This is the story we’re about to tell: how unions roared, how they ruled, how they rotted, and how, like the flight attendants at United Airlines, they sometimes load the revolver, cock it, and then aim squarely at their own mouths. It’s a thriller, a farce, and a cautionary tale rolled into one. And yes, Sports Fans, it’s going to bite like a cobra, so buy your ticket, buckle up, and get ready for this week’s wild ride.

Chapter I – The Founding Fathers of the Picket Line

Before unions, there was hell. Not the sulfur-and-pitchfork kind, but the kind that punched a timecard. Picture the America of the late 19th century: ten-year-olds bent over coal chutes, lungs already sounding like stovepipes; factory floors where children were prized not for their pluck but for their ability to reach into spinning gears; company “benefits” that consisted of a cot that smelled like kerosene and a pine box when the cot no longer did the trick. Pinkertons patrolled the aisles with rifles instead of clipboards, reminding everyone that “open-door policy” meant the trapdoor under your feet. If you filed a grievance, odds were your widow was the one signing it.

The horror stories became headlines. In 1911, the Triangle Shirtwaist fire in Manhattan turned a loft into a crematorium when factory doors were locked “to prevent theft.” A hundred and forty-six immigrant women died, some leaping from the ninth floor rather than burning where they stood. Three years later in Ludlow, Colorado, striking miners and their families dug pits under their tents to hide from gunfire. When guards set the camp ablaze, women and children suffocated underground. By 1921 at Blair Mountain, West Virginia, ten thousand coal miners marched with rifles and red bandanas—one of history’s less romantic origins for the word “redneck.” The companies responded with machine guns and homemade bombs dropped from private planes. Today your boss may ghost you on Slack, but at least he isn’t calling in an airstrike on your cubicle.

This was not “labor unrest.” This was civil war in overalls.

The tremors had begun years earlier. In 1877, after the third wage cut in a year, railroad workers in West Virginia walked off the job. Trains froze in their yards, the strike spread like fire on dry timber, and federal troops restored “order” with rifles, leaving more than a hundred dead. The country had learned its first lesson: steel wheels mattered more than human lungs. Nine years later, Chicago’s Haymarket rally for the radical notion of the eight-hour day ended in an explosion, police bullets, and a show trial that convicted anarchists for the crime of having scary beards. Abroad, May 1st became Labor Day. Here in America, we buried the memory and invented a September barbecue instead.

In 1892, at Homestead, Andrew Carnegie was busy cultivating his reputation as a philosopher-king in Scotland while his henchman Henry Clay Frick imported Pinkertons by barge to crush striking steelworkers. Shots rang out on the Monongahela River, blood slicked the decks, and the strike collapsed. Two years later in Pullman, Illinois, George Pullman’s “model town” revealed itself as a model of exploitation when wages dropped but rents stayed high. Eugene Debs led a strike that shut down rail traffic across the country. The government sent troops; dozens died. Debs went to jail and came out a socialist prophet—a career trajectory LinkedIn no longer offers, though perhaps it should. By 1902, the anthracite coal strike grew so desperate that President Theodore Roosevelt stepped in and, with the air of a man who did not like being cold, forced mine owners and miners to bargain. The miners won shorter hours and higher pay. The owners sulked. Roosevelt emerged as a folk hero.

Even before these explosions, workers had experimented with solidarity. In 1869, a tailor named Uriah Stephens founded the Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor, which sounded more like a Dan Brown novel than a union. They aimed high—abolish child labor, ban prison labor, shorten the workday, impose a graduated income tax. By 1886, nearly a million Americans called themselves Knights. Women and Black workers were sometimes admitted; Asian workers, pointedly, were not. The inclusivity was selective, the secrecy suffocating, and the infighting endless. When Haymarket splattered the movement with anarchist guilt-by-association, membership collapsed. By the 1890s the Knights had become a trivia question.

But the Knights lit sparks. One of their members, Mary “Mother” Jones, left their halls determined to turn labor into a crusade. A grandmother with the temper of a prizefighter, she marched miners’ wives and children into strike lines, daring police to swing their clubs at babies. The press called her “the most dangerous woman in America.” She called herself a hell-raiser. Both were true.

Into the vacuum stepped the builders. Samuel Gompers, cigar smoke curling above his head, founded the American Federation of Labor in 1886. He wasn’t selling utopia; his platform was one word: more. More wages, more leisure, more dignity. Where Gompers used finesse, John L. Lewis used dynamite. A coal miner with the face of Mount Rushmore, he turned the United Mine Workers and later the CIO into industrial battering rams.

Others broadened the fight. A. Philip Randolph organized Pullman porters into the first great Black union, proving that civil rights and labor rights were twin battles. Cesar Chavezcarried the struggle to the fields, leading boycotts and fasting until America had to admit that the grapes on its tables came from hands it preferred not to see. And always lurking in the background was Daniel De Leon, Marxist pamphleteer and eternal killjoy, trying to turn unions into soviets. He never quite succeeded, but he helped spawn the IWW, whose Wobblies waved the red flag and sang about it.

Out of the blood, the strikes, and the endless picket lines came the spoils: the eight-hour day, bans on child labor, overtime, workers’ compensation, the weekend. Not perks dreamed up on a CEO’s yoga retreat, but rights clawed out of graves and contracts signed with trembling hands.

The American middle class—so beloved in stump speeches—wasn’t built on corporate benevolence. It was hammered together by men and women who realized their bosses would kill them, literally, if they didn’t organize. Horror gave rise to resistance; resistance hardened into organization; organization dragged America, kicking and screaming, into regulatory adulthood. Think of it as a coming-of-age story. Only instead of birthday candles, there was machine-gun fire. And instead of cake, dynamite.

Chapter II – When Solidarity Meant Something

America in the early 20th century was an industrial carnival running at full tilt. Electricity lit the skyline, telephones crackled with gossip, and automobiles coughed to life on streets that still smelled of horses. Oil gushed, airplanes leapt, skyscrapers clawed at the clouds. Factories belched smoke, farms mechanized, and meatpacking plants turned livestock into lunch with conveyor-belt efficiency. It was progress with a capital P, and it was fueled by sweat, muscle, and the occasional missing finger.

Boom, Bust, and the Long Slog

World War I gave unions their first taste of real leverage.

Industry needed steady hands, and Washington leaned on management to bargain. Wages rose, hours shortened, and workers glimpsed a future with something more than bread and exhaustion. But peace brought backlash. The Red Scare painted organizers as Bolsheviks in overalls, and employers offered “welfare capitalism” — cafeterias, company bands, even baseball teams — as proof that unions were unnecessary. A pension, a hot lunch, and a softball league: what more could anyone want?

Then came the Roaring Twenties. Radios in every living room, Buicks in driveways, refrigerators humming where iceboxes once stood. Factories churned out not just weapons but dreams, and Americans bought them with gusto. For a moment it seemed everyone was getting rich — until September 29, 1929, when the bottom dropped out like a stage trapdoor.

The Great Depression shredded the illusion. A quarter of the workforce was unemployed, farmers dumped milk in ditches while families starved in cities, and “Hoovervilles” sprouted like weeds. For labor, it was disaster and opportunity rolled into one. Wages collapsed, strikes failed, but anger fermented.

Sit-down strikes spread, hunger marches filled streets, and workers began demanding not just jobs, but rights.

The New Deal: Paper and Promise

Franklin Roosevelt, a patrician with perfect diction and political timing, threw labor a lifeline. The Wagner Act enshrined the right to organize, the Fair Labor Standards Act set minimum wages and maximum hours, and Social Security dangled a safety net. For once, Washington wasn’t sending troops to break strikes — it was signing laws that gave unions legal teeth.

By the late 1930s, the winds of war stirred industry back to life. Europe was burning, and America was fast becoming the workshop of democracy. Factories that had been idle were suddenly deafening; men and women who had been idle now welded wings, stitched uniforms, and riveted tanks.

The Arsenal of Democracy

World War II was the great accelerator. Roosevelt’s “Arsenal of Democracy” wasn’t a slogan, it was a 24-hour racket of steel and sweat: Detroit cranking out B-24 bombers like Fords with wings, shipyards building Liberty ships faster than U-boats could sink them, textile mills spewing uniforms by the acre.

Unions pledged no-strike agreements for the duration — a remarkable act of discipline for organizations born in blood and strikes. In exchange, Washington guaranteed collective bargaining rights and wage stabilization. For a brief moment, management, labor, and government found themselves — miraculously — on the same team.

And on the posters: Rosie the Riveter. Her red bandana, her flexed arm, her confident smirk. She became the symbol of a workforce transformed. Women poured into factories; into roles they’d been told they couldn’t handle. They welded, riveted, drilled, and proved they could build planes as well as pies. Black workers, too, pushed their way into defense industries, fighting both fascism abroad and discrimination at home. A. Philip Randolph threatened a march on Washington in 1941, forcing Roosevelt to sign an order banning racial discrimination in defense plants.

For the first time, America’s factories looked a little more like America.

The Hangover After the Party

But solidarity had its limits.

When the war ended and white soldiers came marching home, the Rosies were handed pink slips and sent back to kitchens with a “thanks, doll, don’t forget the meatloaf.” Black workers, who had broken into industrial jobs by sheer grit, suddenly found “help wanted” signs disappearing again. Unions, while quick to protect white male seniority, rarely lifted a finger for women or minorities. Equal pay, equal rights, and equal treatment wouldn’t show up in earnest until the civil rights and women’s movements decades later.

Solidarity was real — but only if you fit the right description on the hiring card.

Union High Tide

Still, for white men with union cards, the postwar years were nothing short of miraculous.

By the mid-1940s, over one-third of American workers were union members. Wages rose, pensions spread, health insurance became a reality. Families leapt from breadlines to Buicks, from tenements to tract homes. Walter Reuther of the United Auto Workers struck deals that tied wages to productivity — if the company did well, so did the workers. It was the kind of obvious formula that looked like genius because no one had dared try it.

The result was a middle class so solid it became the envy of the world. Union wages bought houses in Levittown, sent kids to college, and put refrigerators, televisions, and cars in reach of millions.

For a shining stretch, the American Dream came stamped “union made.”

Strange Bedfellows

The real shock wasn’t that labor won a few fights — it was that labor and management, mortal enemies since the days of Frick’s hired goons, suddenly decided to sleep in the same bed.

The bosses craved stability, unions demanded security, and Uncle Sam wanted an endless supply of tanks and bullets. Nobody got their fantasy, but everybody got just enough to keep the marriage together — a shotgun wedding officiated by Roosevelt and consummated on the factory floor.

For once, solidarity wasn’t just a word scrawled on a picket sign. It showed up in pensions, paid vacations, Buicks in driveways, and refrigerators that actually hummed instead of wheezed. It wasn’t equality — women and minorities were shown the door the minute G.I. Joe came home — but it was prosperity, at least for the right demographic.

And that’s the punchline: organized labor, after a century of blood, bombs, and broken heads, finally built something that lasted — the American middle class. It didn’t sing like Sinatra or glide like Fred Astaire. It stumbled, swore, smoked three packs a day, and still somehow landed the punch.

For one improbable era, labor actually delivered — not paradise, but a paycheck that cleared.

Chapter III – The Mob Moves In

Unions were supposed to be the noble guardians of America’s working class, the blue-collar guardian angels standing between the guy with the lunch pail and the guy with the yacht.

But give a watchdog the keys to the vault and pretty soon he’s not barking — he’s driving a Cadillac and smoking Havanas. By the 1950s, organized labor wasn’t just compromised. It had gone full Reservoir Dogs. What began as solidarity had become stage-4 pancreatic cancer on the economy: silent, ruthless, and spreading everywhere, with Jimmy Hoffa in the starring role and the mob as executive producers.

Construction was the first act of the farce. The trades — carpenters, masons, electricians, plumbers — should have been labor’s holy trinity. Instead, they became mob franchises. New York’s Concrete Club was less a union and more a Costco for extortion: you want a building? Pay double. Half for the materials, half for the no-show crew “working” the site. Picture a dozen guys leaning on shovels in Queens, collecting checks, never breaking a sweat except deciding who’d grab lunch. That wasn’t corruption. That was the business model. And developers called it Tuesday.

On the docks, the International Longshoremen’s Association turned hiring into a mob-run episode of The Price Is Right. The “shape-up” meant workers literally lined up each morning while union bosses decided who got picked, who got paid, and who got screwed. Spoiler: unless you slipped cash into the right pocket, you were going home hungry. Elia Kazan’s On the Waterfront didn’t exaggerate — if anything, it pulled its punches. Brando may have “had class,” but the real longshoremen had to pay for it.

And then came the Teamsters, the juggernaut of corruption. Under Hoffa, they were the biggest union in the country, 2.3 million strong, and controlling every truck, warehouse, and freight line in America. Hoffa wasn’t a labor leader; he was Tony Montana with a W-2. His masterpiece? The Central States Pension Fund. Between 1960 and 1970, it swelled to $1.5–$2.5 billion — more than $25 billion in today’s money. That’s not a pension fund. That’s a small nation’s GDP. Officially it was for retirements. In reality, it was a mob slush fund with a glossy brochure.

Loans poured into Vegas casinos, Miami hotels, Chicago skyscrapers. Caesars Palace, the Stardust, the Riviera, the Tropicana — all built on the backs of truckers who thought they were saving for shuffleboard in Boca Raton. Every time some guy in plaid shorts pulled a slot machine lever in 1965, he was cashing out a truck driver’s pension. Retirement security had been rebranded as Blackjack 21. By the 1980s, the fund was sucked so dry it made Dracula look restrained, and the feds had to step in. To this day, the Department of Labor babysits the fund, because nobody trusts the AFL-CIO to run a lemonade stand unsupervised. That’s not oversight. That’s a parole officer with a briefcase.

And let’s not pretend this was just “the big guys.” Union corruption trickled down into every sandwich and soda. Picture this: you order a corned beef at a diner in 1960. The butcher’s union skimmed the beef, the vending machine routes were mob-controlled, and the garbage outside was hauled off by a mobbed-up Teamsters local. Congratulations, your lunch just paid the mob three times. It wasn’t dining out. It was revenue sharing.

Of course, fear kept the wheels greased. You didn’t get “disciplined.” You got “chitty-chitty bang-banged.” Victor Riesel, the journalist who exposed union rackets, had acid thrown in his face in 1956 — because nothing says “labor solidarity” like chemical burns. Hollywood fixer Willie Bioff skimmed millions off IATSE contracts until his own guys blew him sky-high. Countless rank-and-file employees who balked at kickbacks ended up floating in rivers, their union cards still in their wallets.

The lesson was clear: solidarity was optional, but death benefits were guaranteed.

And politics? Forget it. Union bosses were practically renting office space in the White House. Campaign contributions, endorsements, envelopes under tables — labor money bought elections as efficiently as it bought Cadillacs. And then came Dallas. November 22, 1963. JFK assassinated, and suddenly all eyes turned to the nexus of unions and organized crime. Hoffa loathed the Kennedys with a passion usually reserved for bad bourbon. Mob bosses like Giancana, Marcello, Trafficante — all tied to union rackets — were seething at Bobby Kennedy’s crusade. And Jack Ruby, who put the final bullet into Oswald, was a Dallas nightclub owner with union-and-mob friends aplenty. Coincidence? Maybe. Or maybe the Central States Pension Fund financed a lot more than Caesars Palace.

By 1975, Hoffa himself became the final cautionary tale. Fresh out of prison, plotting a comeback, he waited outside the Machus Red Fox restaurant for a meeting with Tony Provenzano. A car pulled up. Hoffa climbed in. Curtain down. His body never found, his story never closed. Buried under Giants Stadium? Boiled in acid? Stuffed in a 55-gallon drum? Take your pick. The truth hardly mattered. Hoffa wasn’t just a missing person. He was the metaphor for organized labor itself: swallowed by the corruption it had invited in, erased by the very machine he once ran.

By then, the dream of unions was already dead. What had begun as solidarity became shakedown, what had promised pensions delivered IOUs, and what had once been dignity now came with a juice loan and a parking ticket. The real punchline? The rackets never ended. They just got better lawyers. Today, the mob wears bespoke suits. Instead of pension loans for casinos, it’s private equity gutting companies. Instead of cash envelopes, it’s “consulting contracts.” Same scam, better stationery.

Unions once built the American middle class. Then they sold it off, one paycheck, one pension, one neon palace at a time. And somewhere out there, Jimmy Hoffa is still the ghost at the table, reminding us that solidarity didn’t just lose its bite — it got cement shoes.

Chapter IV – The Golden Goose Gets Slaughtered

The postwar boom was labor’s champagne brunch.

The Arsenal of Democracy had morphed into the Assembly Line of Affluence, and suddenly everyone had Buicks, Frigidaires, and vacations with matching luggage. For once, the unions had delivered: rich contracts, fat pensions, Cadillac health care, and job security that looked ironclad. The golden goose was laying Fabergé eggs, and the middle class strutted like it would last forever.

But success breeds entitlement. Unions forgot that prosperity is fragile, not permanent. What began as bargaining for dignity turned into a mantra of “more, more, more.” More wages, more benefits, more grievance procedures, more restrictive work rules. Seniority became the state religion, and performance pay the devil. Try to discipline a chronic no-show, and the grievance would drag on longer than a Senate filibuster. Try to fire him, and you’d better have a priest on speed dial.

Management caved — at first. Signing larded contracts was easier than a strike. Detroit automakers signed away the store, Pittsburgh’s steel mills chained themselves to obligations they couldn’t sustain, and appliance makers like GE baked unsustainable contracts into their cost structure. Meanwhile, America’s competitors — Germany, Japan, Korea — were rebuilding with lean, automated factories. We stapled COLAs onto contracts while Toyota quietly perfected the Corolla.

By the 1970s, the results were tragicomic. Detroit assembly lines turned into grievance factories. Three men tightened one bolt: one to hold the wrench, one to watch him, and one to file a grievance about safety gloves. Cars rolled off the line with tailpipes rattling off before the first oil change. Detroit still thought it was building Cadillacs. The rest of the world saw lemons with chrome — lemons that needed a prayer, jumper cables, and maybe a priest to get them home from the dealer lot. The only thing produced on time was paperwork for the grievance committee — the Motor City’s hottest growth industry.

Steel fared no better. Mills priced themselves as if girders were spun from platinum. Overseas mills pumped out stronger, cheaper product, and American steel towns turned into post-industrial ghost stories. Youngstown, Gary, Cleveland — once roaring furnaces — looked like the set of an apocalypse movie, minus the popcorn sales. The only sparks left flying were from union leaders still shouting solidarity slogans in empty halls.

Appliances? GE was once proudly American. Today the nameplate belongs to China’s Haier. Shipbuilding? Gone. Furniture? Gone. Electronics? Gone. Textiles? Gone.

The goose hadn’t been stolen. It had eaten itself alive — and then filed a grievance about indigestion.

Meanwhile, the rest of the Rust Belt collapsed in a chorus of grievances. Steel mills gone. Auto plants shuttered. Appliance factories sold to foreign conglomerates. Whole cities hollowed out, while union leaders kept chanting “more, more, more” as if saying it enough would bring the jobs back. Instead, it brought unemployment lines and boarded-up neighborhoods. The goose hadn’t been slaughtered by greedy bosses or evil globalization. It had been smothered by its own keepers, too fat on its own golden eggs to see the blade coming.

And then came the airlines. Once glamorous — Pan Am uniforms, martinis in crystal, the mile-high mystique — by the 21st century airlines ran on razor-thin margins, software-driven schedules, and passengers who would sell their firstborn for an overhead bin. Labor’s playbook? Strikes, slowdowns, sick-outs — hostaging hubs until management blinked. Sometimes it worked. Sometimes it just made automation look sexier. (After all, the only thing scarier to a union than a pink slip is a robot with perfect attendance.)

Consider the split screen. Delta, proudly non-union for flight attendants, is the nation’s largest airline and consistently ranks as a “best place to work.” Why? Pay raises, profit-sharing, boarding pay, and a management culture that figured out something radical: treat employees well without a union telling you to.

Now the other screen: United Airlines flight attendants. Six years without a raise, finally offered a blockbuster deal: immediate pay bumps of nearly 27%, raises up to the mid-40% range over five years, boarding pay copied straight from the Delta handbook, and an hourly pay rate-adjusted retroactive bonus pool worth nearly $600 million. United even booked a $561 million charge in advance, leaving the money sitting on the tarmac with a bow. It was the richest contract in their history, the equivalent of management handing them the keys to the candy store.

And what did they do? They blew their own heads off — with the blessing and inimitable wisdom of the Association of Flight Attendants Union (AFA). Go figure. Seventy-one percent voted it down, after their own representatives had already signed a tentative agreement in good faith. Why? Because they wanted more. They wanted to be paid like pilots, rewarded like mechanics, and respected like executives. Respect? C’mon. The job description requires a high school diploma (or GED), English skills, the ability to lift luggage, serve drinks, hand out pretzels, and say “buh-bye” without snarling. That’s not a Boeing 777 captain landing in a crosswind, a jet engine mechanic rebuilding a turbine, or a senior executive steering a $58 billion company. That’s a customer service safety monitor with a seatbelt.

The punchline? After the contract was rejected — and pulled off the table — United’s share price shot up. Management bought more stock. The $561 million set aside for back pay went straight back into retained earnings. And the union? Their consolation prize was “non-binding mediation talks”… scheduled for March 2026. It took nearly six years to get this far, and now the meter’s running backward.

The only ones applauding louder than United’s board were the AI-powered robots, quietly checking their install dates and wondering how long before they’d be programmed to serve ginger ale at 38,000 feet.

(PS – Sports Fans, stand by and get your popcorn buttered. The United Airlines flight attendants’ saga is so breathtakingly dumb it’s getting its own spotlight in Chapter VIII: “You Can’t Fix Stupid.”)

And here’s the kicker: the more unions squeezed, the more they made automation irresistible. Robots don’t strike. Algorithms don’t file grievances. AI doesn’t demand retroactive combat pay for turbulence. Machines don’t ask for “respect.” They ask for power, software updates, and occasional lubrication. Every strike vote, every sick-out, every “slowdown” didn’t just pressure management — it accelerated the day the robots showed up with timecards. Unions wanted to keep “jobs on the farm,” but the farm just bought a fleet of tractors with Wi-Fi.

Unions may have been necessary when children worked in mines and bosses paid in script. But by the end of the 20th century, the noble caretaker had become the butcher. The goose wasn’t murdered. It committed suicide — and management, globalization, and automation were just the clean-up crew.

Chapter V – PATCO: The Day Reagan Pulled the Trigger

By 1981, organized labor was staggering like a punch-drunk boxer.

Detroit’s factories were rattling out chrome-plated lemons, steel towns were turning into apocalypse sets, and whole industries were packing their bags for Tokyo, Seoul, and Stuttgart. But the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization — PATCO — still believed it was invincible. These were the headset kings of America’s skies, moving 30,000 flights a day. They thought they held the nation hostage: give us more pay, shorter weeks, better conditions, or the planes stop flying.

There was only one problem. Federal employees are flatly barred from striking. Not “sort of,” not “maybe.” Black-letter law. PATCO knew this, but arrogance is a hell of a drug. They bet no president would dare shut down America’s airways. They figured they were holding the gun.

They forgot the president was Ronald Reagan.

On August 3, 1981, 13,000 controllers walked off the job. That afternoon, Reagan strode to the Rose Garden podium, squinting like a cowboy sighting down a rifle. He didn’t need Clint Eastwood’s line — but the menace was the same. He read aloud from the oath every controller had signed:

“I will not participate in any strike against the Government of the United States or any agency thereof. By striking, they are in violation of the law. If they do not report for work within 48 hours, they have terminated their employment.”

Translation: Do you feel lucky today? Well… do ya, punk?

PATCO assumed it was a bluff. Forty-eight hours later, 11,345 air traffic controllers discovered Reagan never bluffed. Fired. Blacklisted. Careers incinerated in the time it takes to sign an executive order.

And the skies? They didn’t collapse. Supervisors, military controllers, and trimmed schedules kept the system afloat. Delays, yes. Chaos, no. The apocalypse PATCO promised fizzled into a drizzle. Reagan pulled the trigger, and the union never got off the mat.

The PATCO Lesson: You’re Not Too Vital to Fire

PATCO wasn’t just a union strike gone wrong. It was a masterclass in hubris. It showed every worker in America that no matter how “essential” you think you are, you can be replaced.

- Railroads and airlines – The Railway Labor Act ties up strikes in mediation and “cooling-off” periods. If pilots, mechanics, or flight attendants walked en masse, they’d discover just how quickly Congress or the President would order them back — or replace them outright.

- Healthcare – Nurses and doctors might feel indispensable, but in a pandemic surge, a walkout wouldn’t look like solidarity. It would look like a hostage crisis. The public wouldn’t cheer. They’d demand replacements, and management would oblige.

- Shipping and ports – Dockworkers have flexed muscle before, but when food, oil, or military shipments stop, presidents from FDR to Nixon have rattled the national security saber.

- Public safety – Police, firefighters, prison guards. In most states, striking isn’t just illegal, it’s career suicide. You walk; you’re gone.

- Energy and utilities – Walk off the job at a power plant or grid, and you won’t just lose your job. You’ll meet federal marshals.

The lesson was elegant in its brutality: in industries where the public can’t live without you, you don’t have leverage. You have a leash.

The Future: Who’s Next?

PATCO’s ghost still lurks in union halls, waiting for the next group arrogant enough to pull the trigger on itself.

- Flight attendants – United’s recent debacle proved the fuse is already lit. Strike nationwide and management — maybe even Washington — wouldn’t blink. They’d bring in contractors, scabs, or worse: robots. In Asia, service bots already roll drinks down the aisle. Japan’s airports test humanoid greeters that never demand retro pay. Rosie the Robot doesn’t glare at passengers for asking for another ginger ale. She also never calls in sick.

- Truckers – Silicon Valley is begging the Teamsters to walk. Autonomous rigs are logging millions of miles in Texas and Arizona. The minute a strike strands freight, Wall Street will fund a driverless trucking armada overnight.

- Healthcare – The surgical robot is already in the OR. AI diagnostic systems already catch more cancers than radiologists. Japan’s elder care bots lift patients without back injuries or overtime. Nurses may think they’re irreplaceable; investors disagree.

- Teachers – Post-COVID, parents have zero patience. AI tutors, VR classrooms, adaptive platforms — already here. In South Korea, AI “assistants” drill grammar. In China, emotion-tracking cameras monitor focus. A national teacher strike in the U.S.? Ed-tech would throw the launch party of the century.

- Telecom and tech – If a data center strike knocked out your Wi-Fi for a week, you’d sign up for Starlink faster than you can reload TikTok. Algorithms already babysit servers; humans just refill vending machines.

History Already Wrote the Ending

This isn’t hypothetical. We’ve already seen it happen.

- Fifty years ago, it took 40–50 crew members to run a tanker. Today, fewer than 20. In Norway, “ghost ships” pilot themselves.

- Railroads once needed platoons of brakemen. Today, a two-person crew runs a mile-long train. Tomorrow it will be one. The day after, none.

- In the 1970s, auto plants employed tens of thousands. Today, robots weld, paint, and assemble without bathroom breaks or union dues.

- Amazon’s warehouses swarm with Kiva bots. Humans are still there — but they’re the assistants now, not the muscle.

Unions know it. Some have even tried to bargain contracts reserving 20–30% of jobs for humans, as if a robot needs a permission slip. Others negotiate severance for AI layoffs, like Las Vegas culinary workers securing $2,000 a year when the machines finally arrive. It’s triage, not strategy.

The Irony, With Teeth

Organized labor once fought automation. Now it fuels it. Every grievance, every sick-out, every strike justifies another capital budget for machines. The only thing scarier to a union than a pink-slip is a robot with perfect attendance.

And here’s the mic-drop:

They’re already in many chairs, and you don’t even see them. They’re just polite enough to wait until you strike before taking your badge.

PATCO thought it was holding the gun. Turns out, the future was holding a circuit board.

Chapter VI – The Public Sector Problem

When private-sector unions slit their own throats, public-sector unions picked up the knife, dipped it in taxpayer blood, and called it “collective bargaining.”

Teachers, cops, firefighters, sanitation crews, postal workers, transit drivers, nurses, professors — the “last bastion” of organized labor. But this bastion doesn’t defend excellence. It defends mediocrity like it’s the Crown Jewels, and hands you the bill.

No CEO in America would sign these contracts. No board would approve them. But politicians do — because they’re not paying with their money. They’re paying with yours.

Bankruptcy as a Business Model

California was ground zero.

- Vallejo (2008) — the first domino, bankrupted by firefighter and police pensions. Average firefighter: six-figure salary, early retirement, lifetime benefits. When the city tried to cut costs, unions squealed, sued, and demanded more. Citizens got fewer cops and fire crews — but paid more for the ones already retired.

- Stockton (2012) — pension obligations ballooned so high that retiree health benefits alone hit $417 million. They slashed them overnight while pensions stayed untouchable.

- San Bernardino (2012) — collapsed under $1 billion in debt, much of it tied to public safety pensions.

And it spread.

- Detroit (2013) — the largest municipal bankruptcy in U.S. history, $18 billion in debt. More than half tied to retiree benefits. Police response times stretched past an hour, streetlights went dark, neighborhoods hollowed — but pension checks still cleared.

- Camden, NJ (2012) — so broke it dissolved its entire police department and rehired under a county force. Crime spiked, pensions kept flowing.

- Scranton, PA (2012) — literally ran out of money and slashed all city employees’ pay to minimum wage. Courts later ordered backpay, nearly bankrupting the city again.

- Central Falls, RI (2011) — pensions for retired cops and firefighters cut up to 55%. It was either that, or total collapse.

- Hartford, CT (2017) — nearly defaulted before a state bailout. More than half its budget eaten by contracts and pensions.

Chicago deserves its own obituary column: teachers’ pensions less than 50% funded, retired principals pulling in over $250,000 a year while classrooms beg for copy paper.

Horror Stories You Can’t Make Up

- Illinois — A retired school superintendent pulls down over $400,000 annually in pension payments. He retired in his fifties. Kids in his district share Xeroxed handouts; he shops for condos in Naples.

- New Jersey — A police captain retired at 49 with a six-figure pension and lifetime health care. He golfs in Florida while Jersey homeowners pay the highest property taxes in America.

- New York — The LIRR overtime king hauled in $344,000 in one year, triple his base pay, mostly through fake shifts. He was indicted. Riders still got fare hikes.

- Massachusetts — A Boston firefighter “too disabled” to climb ladders collected $300k+ thanks to overtime and disability padding. He was later spotted pumping iron at the gym.

- California — Prison guards retire at 50 with six-figure pensions. One takes home $240k a year for life. Sacramento calls it “public safety.” Taxpayers call it robbery.

- New York City — Rubber rooms housed 700+ teachers accused of incompetence, paid six figures to nap for years. Annual cost: $100 million.

- Chicago — Retired school administrators pull pensions of $250,000 a year while neighborhood libraries close.

- Bell, California — City manager paid himself $800,000 a year in a town where the average household earned $40,000. Pension to match.

This isn’t parody. This is policy.

Education: A National Hostage Crisis

Teachers’ unions have gutted public education, turning classrooms into bargaining chips and kids into collateral damage. America spends more per pupil than almost any nation, yet ranks near the bottom in math, reading, and science. The money isn’t buying knowledge. It’s buying pensions in Boca.

- New York City: Rubber Rooms — Over 700 teachers accused of incompetence or misconduct were paid six-figure salaries for years to sit in “reassignment centers,” napping and reading newspapers. Annual cost: $100 million. Kids got substitutes; rubber roomers got paid vacations.

- Chicago Teachers Union — Multiple strikes in the last two decades, shutting down schools for weeks. Demands piled up while enrollment collapsed and pension liabilities soared. Parents fled to charters. Kids fled to the streets.

- Los Angeles Unified School District — $15 billion in retiree health obligations, more than classroom spending. Teachers struck in 2019 anyway. Scoreboard: Pensions 1, Students 0.

- New Jersey — One district spent more on retiree benefits than on current teachers’ salaries. Students learned science from textbooks older than their parents.

- Philadelphia — Schools cut libraries, arts programs, and nurses. Kids bled in classrooms; retirees got cost-of-living raises.

- Nationwide — Tenure rules mean fewer than 0.01% of teachers are ever dismissed for poor performance. Millions graduate functionally illiterate.

The savage irony is, every time unions scream “it’s for the kids,” the kids end up with less.

The classroom isn’t a place of learning. It’s a pension factory with a chalkboard attached.

Public Hospitals & Universities: The Hidden Sinkholes

Hospitals and universities are technically “public service,” but their unions have turned them into black holes that suck in tax dollars, tuition, and patient bills — and spit out bloated pensions, guaranteed overtime, and gold-plated benefits. Patients wait in ER hallways. Students drown in debt. Retirees sip Chardonnay in Miami.

- NYC Health + Hospitals — America’s largest public hospital system, perpetually drowning in debt. Staff contracts guarantee overtime, and step raises the system can’t afford. ER patients wait 12 hours while the union debates who empties the bedpans.

- Cook County Health (Chicago) — Payroll costs eat nearly 70% of the budget. Pension liabilities top $10 billion. Patients get longer waits; retirees get lifetime benefits.

- UC System (California) — Faculty and staff pensions so bloated they’ve added billions in liabilities. One retired administrator pulls $350,000 annually. Tuition doubled in a decade to bankroll it.

- Cal State University — Administrative lifers protected by union contracts pull six-figure pensions without ever teaching a class. Enrollment shrinks, but pensions don’t.

- State Universities Nationwide — In New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Illinois, tuition hikes sold as “investing in students” went straight into retiree benefits. Students borrowed $50k–$100k to fund pensions for professors who retired in the ’90s.

- Massachusetts Hospitals — Unionized nurses earn more in overtime than base pay, padding pensions for life. Patients get higher bills and slower service.

The bitter joke is, that every dollar that could lower tuition or speed up ER care is siphoned into union contracts. Students and patients don’t fund better service. They fund better retirement parties.

Public hospitals and universities are where idealism goes to die — drowned in pension checks, tuition hikes, and overtime scams.

The Savage Truth

Private-sector unions killed their golden goose. Public-sector unions perfected necromancy — a vampire goose hooked to taxpayer IVs, waddling from city to city, honking for more.

Services collapse. Schools rot. Hospitals bleed. Universities drown students in debt. Cities fold. But the pensions never miss a check.

And here’s the gag-and-choke line your readers won’t forget:

It’s not like being snowed in with your mother-in-law. At least she eventually leaves. Public-sector unions don’t. They stay on your couch, raid your fridge, demand another beer, and then send you the bill for their condo in Scottsdale — with lifetime COLAs, healthcare, and golf.

Chapter VII – The Comedy of Errors – The Greatest Hits of Union Stupidity

If the rise of organized labor was once a noble opera, its decline is pure slapstick.

What began as solidarity against Dickensian misery eventually collapsed into a century of farce, a blooper reel where work rules and strikes became so absurd they’d make Mel Brooks blush. Imagine a Tarantino montage scored to “Yakety Sax”: firemen without fires, bartenders with pit crews, and elevator operators pressing “3” while the rest of the world rocketed into the future.

It began with featherbedding. In the golden age of the railroads, unions insisted that every diesel locomotive still carry a fireman — decades after coal-fired engines had gone the way of the dodo. The “fireman” no longer shoveled coal; he shoveled doughnuts while reading the paper, drawing union pay for being ballast. Elsewhere, construction contracts required five men to move one shovel: one to dig, one to supervise, three to stand ready in case the first one tired out. Trucking rules sometimes demanded two drivers for short hauls, one to drive and the other to sit. The point wasn’t efficiency; it was “full employment,” even if “full” meant “fully useless.”

The newspaper business fared no better. Mid-century typesetters in New York strangled an entire industry rather than allow automation. When publishers tried to introduce computerized typesetting in the 1960s, the unions struck, forcing papers to keep using hot-lead machines that belonged in a museum. Entire mastheads — including the New York Herald Tribune — folded, not because readers disappeared, but because the unions fought to freeze time at Gutenberg. They thought they were saving print. They killed it with ink-stained hands.

Meanwhile, Las Vegas perfected its own parody. By contract, pouring a gin and tonic required three bartenders: one to hold the bottle, one to hold the glass, one to supervise the spectacle. The mob skimmed the profits, the unions skimmed the payroll, and tourists sipped watery whiskey sours, wondering why a simple highball needed a pit crew. On the docks of New York and New Jersey, the “shape-up” system was even uglier. At dawn, men lined up for work, cash in hand. Jobs didn’t go to the strongest or the most skilled, but to whoever bribed the union steward. No bribe, no shift. It was extortion with a punch clock. Brando’s On the Waterfront was less art than home video.

Hollywood and Broadway turned featherbedding into performance art. Stagehand unions required two men to plug in a lamp: one to carry the cord, one to supervise the socket. Projectionists were mandated in empty theaters long after automation made them redundant. Broadway producers paid electricians a hundred dollars or more to change a single light bulb. Some film sets employed “standby carpenters,” men paid to linger all day just in case the real carpenter dropped his hammer. Beckett could not have staged it better.

The airlines joined the fun. By the 1970s, mechanics’ unions fought modernization by inventing ghost jobs. Airlines carried men on payrolls to sit in hangars “just in case” a machine broke. They fixed nothing, waited for nothing, and collected checks. No wonder tickets cost more than a mortgage payment until deregulation. Manhattan, meanwhile, continued to employ elevator operators into the 1990s. Their entire job description was saying “Going up?” while pressing “3.” Apartment dwellers paid triple maintenance fees to subsidize men whose role had been automated before Eisenhower left office.

Even the arts weren’t immune. In 1996, the Philadelphia Orchestra went on strike for higher pay, holding out until management folded. The musicians returned triumphant, only to discover their audience had defected permanently to cheaper concerts — or Netflix. They had won the battle and lost their future. And if you think that’s farce enough, consider the Teamsters’ milk strikes of the 1940s and ’50s, which blocked deliveries so thoroughly that entire supplies spoiled. Children went without milk for weeks. Union leaders shrugged: “That’s the price of solidarity.” Public sympathy curdled faster than the cream.

Together, these stories form a grotesque comedy: firemen riding trains with nothing to do, bartenders pouring cocktails like pit crews, typesetters bankrupting newspapers, and elevator chauffeurs pressing buttons in an age of rockets. Each episode plays like comedy, but the punchline is always tragedy. The unions thought they were saving jobs. In reality, they were writing obituaries. They thought they were holding management hostage. What they really held was a gun — pointed squarely at their own heads.

If the labor movement once roared like a lion, by the late 20th century it had become a clown car: honking horns, juggling grievance slips, and drinking overpriced whiskey sours poured by three bartenders at once

Chapter VIII – You Can’t Fix Stupid: The 2025 United Airlines Flight Attendant Contract Saga

Some labor disputes end in blood. Others in bankruptcy. The 2025 United Airlines flight attendant contract ended in something rarer: laughter. Not from the union halls, but from the press, the shareholders, and the public — all of them watching, jaws open, as 27,000 people collectively lit $595 million on fire and called it “solidarity.”

This was supposed to be a triumph. After six years without a raise — six years of sick-outs, picketing, grievance filings, and “solidarity selfies” at O’Hare — United’s Association of Flight Attendants (AFA-CWA, AFL-CIO) had finally squeezed management. The result: a blockbuster deal richer than anything in the airline industry worldwide. Sarah Nelson, their leader and would-be Joan of Arc of organized labor, was poised to declare victory from the ramparts.

Instead, her troops set fire to their own castle.

The numbers were obscene:

- 26.9% average base pay increases on signing day.

- 43–45% step raises over five years.

- Boarding pay that pushed total raises over 50%.

- 401(k) contributions rising to 9% — more than double the U.S. average of 4%, and far richer than what most private-sector workers ever see.

- Paid maternity, parental, and adoption leave.

- Per diem bumps to $2.97 domestic, $3.54 international.

But here’s the crown jewel: every flight attendant was set to receive a lump-sum check for retroactive back-pay covering up to five years at the new rates — checks in the tens of thousands of dollars, in some cases more. Real money. Mortgage-paying money. Retirement-boosting money. The kind of money that changes Christmas mornings.

Now? Nothing. Nada. Zero. Zip. - Not a dime.

And yet, 71% of the membership voted the deal down. Why? Because “we deserve more.”Because “we want more respect.” Because in the fantasy world of the AFA, handing out pretzels and pouring Diet-Coke is apparently the moral equivalent of landing a 777 at night in a thunderstorm, rebuilding an engine in a hangar, or running a $58 billion airline.

The consequences were immediate. The deal evaporated. United pulled it from the table, permanently. Its stock price shot up. Management insiders quietly scooped up more shares. The $561 million already booked for retroactive pay went straight back into retained earnings. And United smiled politely and promised “non-binding mediation talks” in March 2026 — a date so far off and so toothless it might as well have been penciled onto a cocktail napkin.

Sarah Nelson? Silent. The union? AWOL. The flight attendants? Stuck with jumpseats, bitterness, and a very expensive lesson in gravity: stupidity is not protected by collective bargaining.

Split Screen: Delta vs. United

Consider the other screen: Delta Air Lines. Non-union. No AFA. No six-year hostage negotiation. Just steady growth, year after year. In the past decade, Delta has:

- Become the largest airline in the U.S., eclipsing United.

- Rolled out industry-leading profit-sharing — in 2024 alone, employees pocketed billions in bonus checks.

- Consistently ranked as a “best place to work” in surveys of pilots, flight attendants, and staff.

- Raised wages steadily without strikes, slowdowns, or sick-outs.

Delta treats its people well — not because a union told it to, but because it learned that a motivated workforce is a competitive weapon. United, meanwhile, has remained largely static, its crews mired in labor fights, its growth lagging, and its employees now left holding exactly nothing.

Sidebar Chorus

- The Public: “Wait, they turned down five-figure checks? I can’t even get a 401(k) match at my job, and they had 9% locked in? Who does that?”

- The Press (snarky op-ed): “The Association of Flight Attendants has redefined the strike: it’s now a work stoppage against your own paycheck.”

- Shareholders (smiling through champagne): “They just handed us $561 million back. Best labor negotiation in history — and we didn’t even try.”

- A Delta employee (grinning on TikTok): “We just got another profit-sharing bonus. Thanks, United!”

The verdict? United’s flight attendants aren’t martyrs. They’re punchlines.

They didn’t just lose the deal of a lifetime; they handed their competition a recruiting poster. The public rolled its eyes. Shareholders laughed all the way to the bank. And the robots, waiting quietly in the wings, just inched closer to the cockpit door.

Because this saga isn’t just a case study in labor overreach, it’s “Dumb and Dumber” with wings. And here’s the real punchline:

In one vote, United’s flight attendants proved automation isn’t a threat. It’s a mercy. Machines don’t demand “respect.” They just ask for electricity and an occasional software update.

Chapter IX – Corporate Suicide, Labor’s Assisted Death

Once upon a time, a strike could stop a nation cold. When coal miners walked, the lights went out. When autoworkers sat down, Detroit held its breath. Unions had the gun; management blinked first. That movie is over. In the twenty-first century, when labor pulls the trigger, the chamber is empty. Companies don’t plead; they calendar. “Vote no? Fine—see you in 2027.” That’s not brinkmanship. That’s hospice care.

The new playbook is simple: stall, shift, or ship. Stall until the clock runs out on outrage. Shift what you can to right-to-work states where pay follows performance instead of seniority. Ship the rest to places that don’t require a five-man shovel crew and a grievance committee to change a light bulb. You can shout “solidarity” at the loading dock; the cargo just leaves out the back.

Offshoring is the nuclear option—but these days it’s routine. Steel didn’t “disappear”; it took a cheaper flight to Korea and China. Shipbuilding didn’t “die”; it moved to Busan, Nagasaki, and Shanghai, where yards launch more tonnage in a month than we manage in a year. Textiles drifted from Lowell to Greensboro to Dhaka. Furniture left High Point and came back in flat-packs with cartoon wrenches. Electronics vanished into clean rooms you couldn’t find on a globe without nicotine patches. Appliances? Louisville’s pride now answers to Haier. Rubber, glass, bearings, machine tools—gone, gone, gone.

Don’t blame the companies. Blame the greed, corruption, and insensitivity of unions that mistook fat years for forever—contracts that paid people to wait, to watch, to obstruct—until competitors with robots, kaizen, and common sense ate lunch, dinner, and next Christmas.

And when escape abroad isn’t fast enough, automation handles the rest. Robots don’t strike. Algorithms don’t call in “sick.” AI never demands retroactive turbulence pay. Management didn’t get mean; labor got replaceable.

Obituaries of the Fallen (A Selection From a Very Long Page)

American Shipbuilding (1880s–1980s):

- Life: Built the fleets that won WWII; yards from Camden to Richmond hammered steel into victory.

- Cause of death: Work rules that priced a hull like a cathedral. Strikes on the keel blocks while Asia automated.

- Survivors: Hyundai Heavy, Mitsubishi, COSCO.

- Jobs buried: ~600,000.

- Epitaph: From Victory at Sea to Defeat at the Union Hall.

U.S. Steel (1901–1980s):

- Life: Pittsburgh’s crown; girders for skyscrapers and bridges.

- Cause of death: Featherbedding, grievance paralysis, refusal to modernize while Japan and Korea installed basic-oxygen furnaces.

- Survivors: ArcelorMittal, POSCO, Baosteel.

- Jobs buried: ~500,000.

- Epitaph: Forged in fire, smothered in paperwork.

Automobiles (1908–present, limping):

- Life: Motor City built the American dream on wheels.

- Cause of death: Platinum benefits, “jobs banks,” work rules that turned one bolt into three men and a grievance. Quality fell; Toyota smiled.

- Survivors: Toyota/Honda/Hyundai/BMW/Mercedes—non-union plants across the South.

- Jobs buried: Millions since 1970.

- Epitaph: From Motor City to Mortgage City.

Textiles (1800s–1980s):

- Life: Lowell’s looms, Greensboro’s mills, a nation clothed.

- Cause of death: Contracts that made a $5 T-shirt cost $30 to sew; Asia modernized while we memorialized.

- Survivors: Bangladesh, Vietnam, Indonesia.

- Jobs buried: ~1.3 million.

- Epitaph: The loom ran out of thread.

Furniture (1900s–1990s):

- Life: High Point’s handmade pride.

- Cause of death: “Helper” armies, anti-automation rules; particle board priced like mahogany.

- Survivors: China, IKEA.

- Jobs buried: ~250,000.

- Epitaph: Assembly required—overseas.

Consumer Electronics (1920s–1990s):

- Life: Zenith, RCA, Motorola—tubes and transistors made here.

- Cause of death: Unions froze clunky lines; Asia sprinted to semiconductors.

- Survivors: Sony, Samsung, Foxconn.

- Jobs buried: Hundreds of thousands.

- Epitaph: Hot lead, cold corpse.

GE Appliances (1907–2016):

- Life: Louisville’s Appliance Park, twenty thousand badges at the gate.

- Cause of death: Costs calcified by legacy contracts.

- Survivors: Haier, LG, Samsung.

- Jobs buried: Tens of thousands.

- Epitaph: Still humming—just not here.

Pan Am, TWA, Eastern, Braniff (1927–2001):

- Life: White-glove glamour at 35,000 feet.

- Cause of death: Sky-high labor costs meeting deregulation’s gravity.

- Survivors: Delta, Southwest, Emirates.

- Jobs buried: Hundreds of thousands.

- Epitaph: Final boarding call—permanent delay.

Rubber & Tire (Akron, 1900s–1980s):

- Life: Firestone, Goodrich, Goodyear—The Rubber City.

- Cause of death: Strikes and wage spirals as global rivals scaled up.

- Survivors: Michelin, Bridgestone.

- Jobs buried: Hundreds of thousands.

- Epitaph: Blown out.

Newspapers & Printing (1800s–2000s):

- Life: The Fourth Estate’s ink-stained army.

- Cause of death: Typographers blocking automation; hot-metal romance versus cold reality.

- Survivors: Digital publishers (mostly non-union).

- Jobs buried: Tens of thousands.

- Epitaph: Stop the presses—forever.

Trucking (Teamster cartel era → 1980 deregulation):

- Life: Teamsters ruled the interstates.

- Cause of death: Corruption, mob tax, and inflexibility; deregulation smashed the cartel.

- Survivors: FedEx, UPS, Amazon’s non-union fleets.

- Jobs buried: Hundreds of thousands (and many re-born—without the union).

- Epitaph: Strong union. Weak pulse.

Union-heavy Supermarkets & Retail (1950s–2000s):

- Life: A&P, Dominick’s, a thousand hometown chains.

- Cause of death: Wage/benefit loads Walmart and Costco turned into market share.

- Survivors: Walmart, Target, Amazon.

- Jobs buried: Hundreds of thousands.

- Epitaph: Paper or plastic? Neither survived.

Heavy Equipment & Industrial Manufacturing:

- Life: Caterpillar, International Harvester, Ingersoll—iron and diesel.

- Cause of death: Strike-prone plants, antique rules; rivals adopted lean.

- Survivors: Komatsu, Volvo, Toshiba, Hyundai

- Jobs buried: Tens of thousands.

- Epitaph: Machines rust; contracts ossify.

Ports & Longshore (mid-1900s–present):

- Life: The nation’s arteries.

- Cause of death: “Shape-ups,” featherbedding, slowdowns; containerization + automation did the rest.

- Survivors: Hyper-automated ports in Asia and Europe.

- Jobs buried: Hundreds of thousands.

- Epitaph: Container arrived. Job departed.

Coal Mining (1800s–present, shriveled):

- Life: Fuel of the century.

- Cause of death: Strike waves, pension bombs, tech stagnation; gas and renewables took the market.

- Survivors: Cheaper fuels and cleaner tech.

- Jobs buried: Millions over a century.

- Epitaph: Went out not with a bang, but a grievance.

Hostess Brands (1919–2012, resurrected without the baggage):

- Life: Twinkies, Hostess Cupcakes and Wonder Bread.

- Cause of death: Union gridlock → liquidation; brands sold, jobs vaporized.

- Survivors: Private equity.

- Jobs buried: ~18,000.

- Epitaph: Let them eat… asset sales.

We could keep going. We could wallpaper a terminal with these.

The Death of American Towns: A Funeral Procession

It wasn’t just factories that died; towns did. Main Streets turned into boarded dioramas. Ballfields overgrew. The union hall kept the lights on; the rest of the zip code went dark.

Detroit, Flint, Pontiac, Saginaw, Lansing, Battle Creek, Grand Rapids, Youngstown, Warren, Akron, Dayton, Toledo, Lorain, Cleveland, Steubenville, Canton, Zanesville, Pittsburgh, Johnstown, Bethlehem, Allentown, Reading, Erie, Scranton, Wilkes-Barre, Utica, Schenectady, Troy, Syracuse, Rochester, Buffalo, Niagara Falls, Camden, Paterson, Newark, Trenton, Jersey City, Bridgeport, Waterbury, New Haven, Providence, Pawtucket, Fall River, Lowell, Lawrence, Lynn, Worcester, Holyoke, Springfield, Manchester, Concord, Burlington, Gary, Hammond, East Chicago, Rockford, Peoria, Decatur, Springfield (IL), Moline, Quincy, Evansville, Terre Haute, South Bend, Elkhart, Fort Wayne, Milwaukee, Racine, Kenosha, Green Bay, Madison, Duluth, Superior, Minneapolis, St. Paul, St. Louis, East St. Louis, Kansas City (KS & MO), Omaha, Lincoln, Wichita, Tulsa, Oklahoma City, Muskogee, Shreveport, Monroe, Baton Rouge, Lake Charles, Mobile, Birmingham, Montgomery, Huntsville, Gadsden, Chattanooga, Knoxville, Nashville, Memphis, Jackson, Little Rock, Pine Bluff, Texarkana, Houston’s East End, Galveston, Corpus Christi, Beaumont, Port Arthur, Lubbock, Amarillo, Odessa, El Paso, Albuquerque, Santa Fe, Oakland, Richmond (CA), Vallejo, Stockton, Modesto, Fresno, Bakersfield, Visalia, Salinas, Watsonville, Oxnard, San Bernardino, Riverside, Barstow, Palm Springs, Las Vegas (pre-corporate), Reno, Carson City, Salt Lake City, Ogden, Provo, Boise, Spokane, Tacoma, Everett, Yakima, Longview, Astoria, Portland, Eugene, Medford, Billings, Butte, Helena, Missoula, Casper, Cheyenne.

That’s not exhaustive. That’s a sampler. Each one once put its name on a water tower in twenty-foot letters. Now too many are drug-gnawed dystopias where the old factory is a set piece, and the new industry is Narcan. The mills shut. The tax base evaporated. The parks filled with weeds; the schools with empty chairs. The American Dream didn’t vanish; it was pawned to keep a grievance committee funded one more contract cycle.

Think about it Sports Fans - If it happened there, why not here? Why not to your kids? Why not to the town with your name on the water tower?

The Lesson (Delivered Without Novocaine)

Unions once saved workers from Dickensian cruelty. Then they mistook victory for permanence—turning protection into predation. They demanded “more, more, more” until the math snapped. They strangled modernization, mocked merit, bankrupted employers, and dared management to say the quiet part out loud.

Management finally did. We’re not negotiating with gravity. We’re leaving.

So, they left. First the factories. Then the paychecks. Then the families. Then the towns. Companies didn’t die; they relocated. The work didn’t vanish; it arrived in Tennessee, Tijuana, or Taipei with better quality and fewer committees. The goose wasn’t murdered by globalization; it was assisted to the exit by the very hands sworn to guard it.

Organized Labor wanted leverage. It got a lever. It just didn’t notice it was attached to the trap door beneath its own feet.

Chapter X – Where Unions Still Matter (Barely)

For most of the American economy, unions are a bit like an 8-track tape deck: fascinating relics, fun to explain to your kids, but mostly useless unless you want to hear Disco Inferno with all the fidelity of a blender.

The factories are gone, the golden goose has long since been plucked and roasted, and yet, somewhere in the corner, unions still twitch — not dead, not alive, just embalmed with dues.

Still, there are places — very narrow, very specific corners — where organized labor’s ghost hasn’t entirely lost its pulse. Where the scales tilt so badly toward management that without some collective pushback, workers would be one Excel spreadsheet away from collapse. But here’s the twist: these aren’t shining examples of solidarity.

They are exceptions that prove the rule - like cockroaches surviving a nuclear blast.

Healthcare: Hedge Funds with Scrubs

Hospitals today are less Florence Nightingale and more Goldman Sachs in lab coats.

Payroll is the fattest line on the spreadsheet, which makes nurses, aides, and techs the juiciest targets for “cost containment.” Left alone, administrators would happily schedule 16-hour shifts back-to-back and call it “efficiency.” So, yes, a measure of protection is warranted — not to finance retirement villas in Boca, but to make sure the nurse holding your IV isn’t hallucinating from exhaustion. The problem? Healthcare unions too often blow that moral high ground, demanding Cadillac benefits for lifers and shielding incompetents who make Doogie Howser look like Dr. House.

Construction: Coffins in Concrete

Mega-projects — skyscrapers, tunnels, bridges — are feats of human ambition where one missed weld can mean ten funerals.

Here, the idea of collective safety standards actually matters. Workers need leverage to keep bosses from cutting corners that bury men alive in rebar. But then the rot seeps in: no-show jobs, ghost paychecks, mobbed-up bid rigging. A $10 million bridge suddenly costs $20 million, and taxpayers foot the overrun while “safety stewards” collect six figures for holding a clipboard.

Useful? Occasionally - Honest? Rarely.

The Gig Economy: Dickens with Wi-Fi

If there’s a frontier crying out for a new kind of union, it’s this one.

Uber drivers, warehouse pickers, app-based couriers — “independent contractors” in name, disposable widgets in practice. The algorithm decides when you eat. Try calling in sick to Siri. Collective bargaining here wouldn’t be nostalgic; it would be revolutionary. But where are the unions? AWOL. Too busy lobbying for bloated pensions in Illinois to care about the warehouse worker whose bathroom breaks are tracked by GPS.

The irony is thick enough to spread on toast: unions could have been reborn in the gig age. Instead, they missed the gig entirely.

Exceptions That Prove the Rule

So yes, there are places where worker protection still matters.

Healthcare. Construction. Gig work. The problem is, the unions we’ve got are the wrong tool for the job. They don’t fix the abuses; they feed on them. They don’t defend the workers; they defend the dues. They don’t adapt to new realities; they cling to the same bloated playbook that already bankrupted half the towns in America.

The American worker doesn’t need another featherbedded bureaucracy with a logo. They need guardrails that stop corporations from treating them like rented mules without turning the mule barn into Versailles. The current unions aren’t those guardrails. They’re speed bumps with mob ties.

Which leaves us with the question that matters: if not unions, then what?

Chapter X – What Would Frank Do?

For ten chapters we’ve performed the autopsy. Unions promised dignity, delivered dysfunction, and left the body riddled with grievance slips, IOUs, and bloated pensions in Boca. But the question isn’t “Do we need unions?” The real question is: How do you make unions irrelevant?

Not with hired thugs. Not with dusty Pinkerton tactics. Not with lawyers billing $1,500 an hour to write anti-union memos that nobody reads. The most lethal strategy isn’t busting at all. It’s building. Build a workplace so fair, so rewarding, so relentlessly decent that no organizer with a clipboard can sell snake oil in your parking lot. That’s the secret. That’s the sauce. That’s the doctrine.

And it comes down to the Glassnerian Theorems — ten commandments of culture, forged in the smoke-filled boardrooms and picket lines of American business. They’re ironic, yes. Funny, often. But ironclad. They’re how you inoculate your company without a needle.

The Glassnerian Theorems: Ten Commandments of Union Immunity

- Pay Competitively: Not lavishly, not cheaply — smartly. Enough so employees don’t peek over the fence. Costco does it. Publix does it. Delta does it. Walmart wishes it did.

- Reward Performance, Not Tenure: Seniority is the union’s Holy Grail. Smash it. Pay and promote for results. Salesforce, Nvidia, Microsoft — meritocracies where effort is currency.

- Design Benefits Like an Adult: Robust, sustainable, flexible. Healthcare that matters. Retirement that lasts. Delta’s flight attendants keep voting “no” because the company already listens.

- Share the Wealth: Profit-sharing, stock options, gainsharing. Southwest’s culture is inoculated not by slogans, but by checks employees can cash.

- Communicate Relentlessly: Rumor is the union’s oxygen. Kill it with facts. Patagonia publishes open letters. Costco tells employees the margins. It works.

- Train Thy Managers: Bad bosses are union recruiters in disguise. Trader Joe’s figured it out. Toyota’s U.S. plants figured it out. Most companies still haven’t.

- Respect Time and Dignity: Schedules, breaks, flexibility — treat people like adults, not pawns. If you don’t, the union shows up faster than Amazon Prime.

- Never Overpromise: Don’t fake “competitive pay” when you’re bottom quartile. Don’t sell “career ladders” to nowhere. Own the narrative, or the union will.

- Design Jobs for Pride and Ownership: People want to matter. Publix employees brag about ownership. Tesla line workers brag about innovation. That pride is kryptonite to organizers.

- Never Let a Union Organizer Tell Your Story: If employees hear about their worth from outsiders, you’ve already lost. Amazon shows the cost of fear. Delta shows the payoff of trust.

The Magic Formula

Culture isn’t inoculated - It’s cooked.

A sauce reduced over time: respect, fair pay, shared upside, honest communication, pride of purpose. Get the recipe right, and you don’t need inoculation. You get immunity.

Sniffing Trouble Before It Stinks

Rot doesn’t arrive overnight. It seeps in. You can smell it if you pay attention:

- Silence where chatter used to be.

- “We” becomes “they.”

- Anonymous complaints spike.

- New “friends” in the breakroom.

- Sudden flu outbreaks right before bargaining.

- Parking lot caucuses after shifts.

- Social media smoke on TikTok and Reddit.

- The whisper network hums louder than the intercom.

Unions aren’t magic. They’re mold. And like mold, they grow in cracks you refused to seal.

What To Do When the Rot Appears

- Don’t panic — fear proves the union’s case.

- Engage directly — broken A/C has started more campaigns than Marx.

- Fix easy stuff fast — small wins kill big grievances.

- Audit managers — bad bosses mint more union cards than organizers.

- Kill rumors with facts — silence is gasoline.

- Show up — don’t vanish into mahogany; walk the floor.

- Level with people — pain is tolerable, spin is not.

- Find your culture carriers — lose them and you’re toast.

The Whisperer’s Closing

Unions don’t organize great companies. They organize cracks, neglect, and arrogance. They thrive when leaders hide, when managers bully, when culture rots. But here’s the whisper: follow the Glassnerian Theorems, and you don’t fight unions. You starve them. You make them irrelevant.

Because, in the end, nobody cares more about your employees than you should. And if you can’t prove that every single day, someone else will show up with a clipboard and promise to.

So, make your company the place where employees fight for you, not against you. Make it the best place to work — the one unions hate because they can’t crack it. And when you do, Sports Fans, you won’t need a lawyer, a lobbyist, or a labor negotiator.

You’ll just need to look in the mirror, smile, and whisper to yourself:

“That’s what Frank would do.”

Chapter XI - The Veritas Way

Unions weren’t supposed to be permanent. They were supposed to be training wheels — a guardrail until management learned to ride the bike of fairness. But instead of stepping off when the road straightened, they welded themselves to the frame and demanded gas money.

The Veritas Way is about finally removing the training wheels. If you lead with clarity, measure with data, and care with a calculator, you don’t need unions. And if you have them? You can show them the door. There’s no law that says they’re forever. They have to be voted in, and they can be voted out.

Governance as Clarity

Every contract accountable to math, not mythology. Every clause traceable, every promise priced, every “benefit” tethered to reality. No IOUs hidden in pension vaults. No “lifetime health care” clauses drafted like fairy tales.

Boards should read pay plans like a pilot reads a preflight checklist: line by line, fail-safe by fail-safe. If the numbers don’t fly, the plane doesn’t leave the gate.

Mythology makes martyrs. Math makes sense.

Data Beats Noise

Noise is the union’s fertilizer: rumors, grievances, whisper campaigns. The Veritas Way kills it with sunlight.

Productivity is not a vibe. It’s a metric. Pay is not a slogan. It’s a formula. When data runs the room, organizers starve.

Delta proved this: no union for flight attendants, yet the best pay and profit-sharing in the business. Publix employees own their company stock and laugh off organizers. Trader Joe’s survives not because it’s quirky, but because employees trust the ledger matches the lip service.

You can’t spin your way past data. You either deliver, or you don’t.

Compassion with a Calculator

Here’s where the unions had a point. Workers aren’t widgets. Dignity matters. But compassion without arithmetic is bankruptcy.

The Veritas Way is compassion that’s measured: health care, yes — sustainable health care. Retirement, yes — but funded, not fantasy. Leave policies, yes — but aligned with productivity, not against it.

Compassion doesn’t mean Santa Claus. It means fairness you can afford.

If You Do It Right, You Don’t Need Unions

The greatest irony? When companies actually lead with The Veritas Way, unions become obsolete.

- Delta: Non-union flight attendants make more than their unionized peers at United, with boarding pay and bonuses.

- Publix: Employee-owned, culture-driven, proudly non-union.

- Trader Joe’s: Above-market pay, dignity in scheduling, and a culture so strong organizers can’t get traction.

- Costco: Pays better than Walmart, with retention rates that make unions irrelevant.

When leaders govern like adults, employees don’t want outsiders. They’re already insiders.

And If You Have Them? You Can Vote Them Out

This is the part unions don’t put in their brochures: membership is not forever.

- Detroit auto suppliers: Several plants decertified in the 1990s when employees realized union dues didn’t stop job losses.

- Las Vegas casinos: Culinary locals have been voted out in smaller properties where management shared profits directly.

- Southern manufacturing plants: From textiles to tires, dozens of facilities have decertified in the last 20 years when companies offered better pay and clarity than unions could.

- Healthcare: Several hospitals, including in Florida and Texas, voted unions out after years of “representation” produced nothing but dues bills.

The law is clear: if 30% of employees petition, a decertification vote must happen. If a majority votes no, the union vanishes.

Unions know this. It’s why they fight so hard to keep employees in the dark.

How to Kick It

So, here’s how you inoculate — and, if needed, evict:

- Do the basics better than the union could. Pay fairly. Be transparent. Don’t give them oxygen.

- Educate employees on their rights. They voted the union in. They can vote it out. No fine print.

- Make the case every day. If you run the company with dignity, the organizer’s pitch sounds like a scam email from a Nigerian prince.

- If they’re already in the house, turn the lights on. Show employees the math: dues in, crumbs out. Then show them what they’d gain by taking control.

The Whisperer’s Closing

Unions aren’t gods. They’re tenants. And tenants can be evicted.

The Veritas Way is the landlord’s notice: govern with clarity, measure with data, care with discipline, and employees will realize they never needed a middleman to fight their battles. They already had a leader who gave them everything worth fighting for.

So, here’s the closer, Sports Fans: Unions get voted in. They can get voted out. The only permanent contract is the one you write every day with your people — not on paper, but in culture, pay, and trust.

Do that right, and you won’t just avoid unions. You’ll make them look like what they really are: a relic, a tax, a bad habit.

And when that vote comes? Don’t just open the door for them. Hold it. Smile. Whisper: “Thanks for stopping by. Don’t let it hit you on the way out.”

Epilogue – The Echo of a Roar

Once upon a time, unions were lions. They roared through steel mills, shipyards, coal seams, and assembly lines. They scared bosses, they shook governments, they made history. But lions don’t stay lions forever. Somewhere between the Cadillac contracts, the no-show jobs, and the pension checks mailed to Boca, the roar faded.